By: Arturo Perea Martínez, Internal Medicine-Pediatrics Hospital Nutrition Unit. National Institute of Pediatrics. Lilia Mayrel Santiago Lagunes, Nutritionist. Specialist in Pediatric Clinical Nutrition. Hospital Nutrition Unit. National Institute of Pediatrics. Paul Tadeo Ríos Gallardo, Nutritionist. Hospital Nutrition Unit. National Institute of Pediatrics. María José Pecero Hídalgo, Pediatrician Hospital Nutrition Unit. National Institute of Pediatrics. Sis Eunice Arce Monroy, Nutritionist. Obesity and Non-Communicable Diseases Clinic. National Institute of Pediatrics Aranza Lilián Perea Caballero, Nutritionist. Fundación de investigaciones sociales, A. C.

Introducción

The interaction between nutritional status and systemic immune response has been established for decades. Optimal nutritional status is associated with a better immune response, while conditions that compromise nutritional health contribute to a higher risk of infectious diseases, their clinical course, and prognosis.

Globally, children experience one or more forms of malnutrition that affect their health and development (1 – 3).

The immune system integrates two fundamental response mechanisms: the innate and the adaptive immune responses. Various factors regulate these functions, with adequate nutritional status being crucial for the development, maintenance, and expression of the immune response (4 – 6).

Vitamins and minerals regulate and modulate all stages of the immune response, so a deficiency in one or more of these micronutrients can affect both, favoring a state of greater vulnerability of the host to infections of any type (7 – 9).

The immune system and its association with nutritional status.

Children with undernutrition have an increased risk of dying from infectious diseases. Undernutrition has been considered the underlying cause of 45% of child deaths; that is, it is estimated to be a direct or indirect factor in just over 3 million deaths of children under 5 years of age.

Immune deficiency associated with malnutrition leads to (10):

a. Impaired intestinal barrier function

b. Reduced exocrine secretion of protective substances

c. Low levels of plasma complement

d. Structural changes in lymphatic tissue

e. Retarded delayed-type hypersensitivity responses

f. Reduced levels of antibodies produced after vaccination

g. Cytokine patterns skewed toward a Th2 response

Immunizations are considered the most effective public health intervention strategy for containing morbidity and mortality from infectious causes (10). The humoral and cellular immune response achieved with immunizations has an individual profile that is determined, among other things, by the following factors:

a. Host. Age, sex, genetics, and the presence of any acute or chronic condition.

b. Vaccine. Vaccine-related factors include type, schedule, dose, adjuvants, route of administration, and quality of the biological product.

c. Perinatal stage. The pregnant woman’s biological and nutritional status, gestational age, birth weight, breastfeeding, and maternal immunity.

d. Microbiological regulation. Pre-existing immunity, microbiota, infections, and antimicrobial use.

e. Habits. Alcohol or tobacco consumption, stress, physical exercise, and sleep quality.

f. Environment and culture. Seasonality, geography, and family size.

g. Nutrition. The influence of nutritional status on immunity and response to vaccination is mediated by factors such as body mass index (BMI), nutritional status, and micronutrient intake (zinc, vitamins A, D, E, and C).

Impact of nutritional status on vaccine-induced immunity

Undernutrition

The type and severity of undernutrition affect various immunological pathways. Protein-energy malnutrition affects both innate and adaptive immunity by reducing lymphocyte proliferation, impairing T-cell function, and decreasing the production of specific antibodies and the memory response.

Deficiencies in vitamin A, zinc, and iron further impair host immunity by altering mucosal integrity, modifying cytokine production, and reducing the synthesis of neutralizing antibodies.

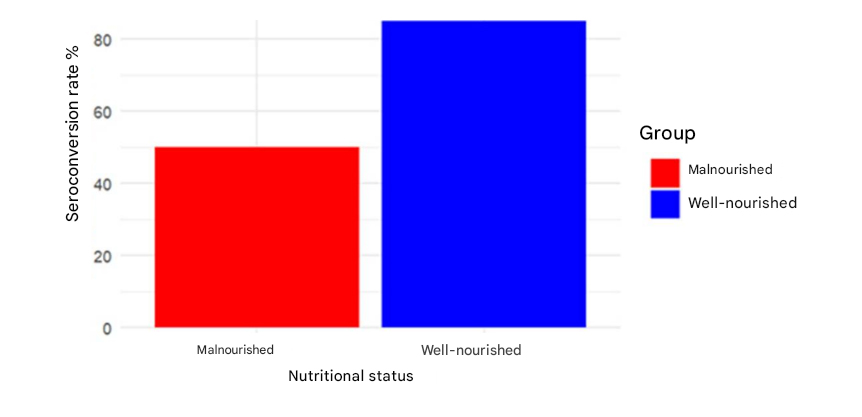

Therefore, vaccines against poliomyelitis, measles, and rotavirus exhibit reduced immunogenicity and lower seroconversion rates in children with these nutritional conditions (11-15).

Seroconversion rates for oral polio vaccine (OPV) in undernutrition (undernutrition) children versus well-nourished children (14).

Other studies have shown that malnourished children have lower antibody responses to the hepatitis B, MPVS, measles, polio, pertussis, salmonella and tetanus vaccines (16-19).

Micronutrients

In a prospective study of 300 infants aged 6 months to 5 years, the effect of micronutrient supplementation prior to immunization with various vaccines was evaluated. Serum levels of vitamin A, zinc, vitamin D, and iron were measured before and after supplementation. Antibody titers against the DTP, MMR, hepatitis B, and pneumococcal vaccines were assessed by ELISA before and between 4 and 6 weeks after vaccination. The results showed that children in the intervention group exhibited significantly greater improvements in serum micronutrient levels and increased seroconversion rates for all vaccines studied (DTP: 90% vs. 77%; MMR: 91% vs. 72%; Hepatitis B: 95% vs. 79%; Pneumococcal: 88% vs. 71%; p < 0.01). Mean antibody titers after vaccination were between 30% and 40% higher in the intervention group. Regression analysis confirmed that vitamin A and zinc are strong positive predictors of vaccine response (20).

Studies in children have not found any association between vitamin D levels or supplementation with antibody responses to the trivalent influenza vaccine; however, they do show a tendency towards a decrease in antibody responses following administration of the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine.

Supplementation with vitamins A and D results in more intense tuberculin skin reactions and a lower interferon response following BCG vaccination.

Vitamin A administered concurrently with the measles vaccine at 6 months of age leads to a decrease in the seroconversion rate only in infants with maternal antibodies (21-47).

Overweight and Obesity

Numerous studies in adults demonstrate that an increase in BMI is inversely correlated with antibody responses to hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccination (47). Following vaccination with the trivalent influenza vaccine, initially, an increase in BMI correlated with greater antibody responses. However, twelve months after vaccination, a higher BMI was associated with a lower antibody response, and obese individuals also showed fewer specific CD8 T cells and less interferon-gamma production (47).

Conclusions

The immune response is influenced by various external and internal factors.

Nutrition is one of the most important regulatory factors of the immune system and its functions.

Integrating nutritional assessment and support into immunization programs could improve outcomes in resource-limited settings and strengthen herd immunity.

Micronutrient supplementation and improved nutrition significantly increase the immunogenicity of vaccines in early childhood.

References

1. World Health Organization. The global health observatory: joint child malnutrition estimates (UNICEF-WHO-WB) [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2024. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/joint-child-malnutrition-estimates-unicef-who-wb Citado 26 de septiembre de 2025.

2. World Health Organization. Malnutrition [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2024. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition Citado 26 de septiembre de 2025.

3. UNICEF. Child malnutrition [Internet]. New York: UNICEF; 2024. Disponible en: https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/malnutrition/ Citado 26 de septiembre de 2025.

4. Pecora F, Persico F, Argentiero A, Neglia C, Esposito S. The Role of Micronutrients in Support of the Immune Response against Viral Infections. Nutrients. 2020 Oct 20;12(10):3198. doi: 10.3390/nu12103198.

5. Maggini S, Maldonado P, Cardim P, Fernandez Newball C, Sota Latino ER. Vitamins C, D and Zinc: Synergistic Roles in Immune Function and Infections. Vitam Miner. 2017;6. doi: 10.4172/2376-1318.1000167.

6. Calder PC. Conference on “Transforming the nutrition landscape in Africa”. Plenary Session 1: Feeding the immune system. Proc Nutr Soc. 2013;72(2):299-309. doi: 10.1017/S0029665113001286.

7. Bresnahan KA, Tanumihardjo SA. Undernutrition, the acute phase response to infection, and its effects on micronutrient status indicators. Adv Nutr. 2014 Sep;5(5):702-11. doi: 10.3945/an.114.006361.

8. Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Factors that influence the immune response to vaccination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019 Mar 13;32(2):e00084-18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00084-18.

9. Ngoie Mwamba G, Kabamba Nzaji M, Luboya Numbi O, Ali Mapatano M, Lusamba Dikassa PS. Micronutrient and protein-energy supplementation enhance vaccine responses in undernourished children: Evidence from a systematic review. F1000Res. 2025 Sep 11;14:507. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.164227.4.

10. Beiersmann C, Bermejo Lorenzo J, Bountogo M, Ye M, Tiendrébéogo J, Louis VR, et al. Malnutrition determinants in young children from Burkina Faso. J Trop Pediatr. 2013 Oct;59(5):372-9. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmt037.

11. Hoest C, Seidman JC, Pan W, Ali A, McDermid J, Mølbak K, et al. Evaluating associations between vaccine response and malnutrition, gut function, and enteric infections in the MAL-ED cohort study: methods and challenges. Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Nov 1;59 Suppl 4:S273-9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu611.

12. Mwamba GN, Nzaji MK, Hoff NA, Mukamba RM, Kasongo JM, Kabamba AN, et al. Nutritional status link with polioseronegativity among children from poliomyelitis transmission high-risk area of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). J Multidiscip Healthc. 2024 Mar 21;17:1219-29. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S437351.

13. Tripathy SK, Das S, Malik A. Vaccine and malnutrition: A narrative review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2023 Sep;12(9):1808-13. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_596_23.

14. Reuman PD, Kubilis P, Hurni W, Brown L, Nalin D. The effect of age and weight on the response to formalin inactivated, alum-adjuvanted hepatitis A vaccine in healthy adults. Vaccine. 1997 Jun;15(9):1157-61. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00310-6.

15. Halsey NA, Moulton LH, O’Donovan JC, Walcher JR, Thoms ML, Margolis HS, et al. Hepatitis B vaccine administered to children and adolescents at yearly intervals. Pediatrics. 1999 Jun;103(6):1243-7. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1243.

16. Sheridan PA, Paich HA, Handy J, Karlsson EA, Hudgens MG, Sammon AB, et al. Obesity is associated with impaired immune response to influenza vaccination in humans. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012 Aug;36(8):1072-7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.208.

17. Talbot HK, Coleman LA, Crimin K, Zhu Y, Rock MT, Meece J, et al. Association between obesity and vulnerability and serologic response to influenza vaccination in older adults. Vaccine. 2012 Jun 22;30(30):3937-43. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.071.

18. Gupta S, et al. Nutritional Strategies to Enhance Vaccine Efficacy in Infants and Young Children. Eur J Cardiovasc Med. 2025;15(1):472-6.

19. el-Gamal Y, Aly RH, Hossny E, Afify E, el-Taliawy D. Response of Egyptian infants with protein calorie malnutrition to hepatitis B vaccination. J Trop Pediatr. 1996 Jun;42(3):144-5. doi: 10.1093/tropej/42.3.144.

20. Mohammed I, Damisah MM. The immunological response to polyvalent meningococcal vaccine in Bauchi State, Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1982;76(3):351-3. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(82)90188-2.

21. Salimonu LS, Johnson AO, Williams AI, Adeleye GI, Osunkoya BO. Lymphocyte subpopulations and antibody levels in immunized malnourished children. Br J Nutr. 1982 Jul;48(1):7-14. doi: 10.1079/bjn19820082.

22. Idris S, El Seed AM. Measles vaccination in severely malnourished Sudanese children. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1983 Mar;3(2):63-7. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1983.11748270.

23. Powell GM. Response to live attenuated measles vaccine in children with severe kwashiorkor. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1982 Dec;2(4):143-5. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1982.11748247.

24. Gaayeb L, Pincon C, Cames C, Sarr JB, Seck M, Schacht AM, et al. Immune response to Bordetella pertussis is associated with season and undernutrition in Senegalese children. Vaccine. 2014 Jun 5;32(27):3431-7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.03.086.

25. Suskind R, Sirishinha S, Vithayasai V, Edelman R, Damrongsak D, Charupatana C, et al. Immunoglobulins and antibody response in children with protein-calorie malnutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1976 Aug;29(8):836-41. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/29.8.836.

26. Brussow H, Sidoti J, Dirren H, Freire WB. Effect of malnutrition in Ecuadorian children on titers of serum antibodies to various microbial antigens. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995 Jan;2(1):62-8.

27. Harland PS. Tuberculin reactions in malnourished children. Lancet. 1965 Oct 2;286(7414):719-21.

28. McMurray DN, Loomis SA, Casazza LJ, Rey H, Miranda R. Development of impaired cell-mediated immunity in mild and moderate malnutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981 Jan;34(1):68-77. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.1.68.

29. Ziegler HD, Ziegler PB. Depression of tuberculin reaction in mild and moderate protein-calorie malnourished children following BCG vaccination. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1975 Jul;137(2):59-64.

30. Sadarangani SP, Whitaker JA, Poland GA. “Let there be light”: the role of vitamin D in the immune response to vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015 Dec;14(12):1427-40. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.1082426.

31. Sundaram ME, Talbot HK, Zhu Y, Griffin MR, Spencer S, Shay DK, et al. Vitamin D is not associated with serologic response to influenza vaccine in adults over 50 years old. Vaccine. 2013 Apr 19;31(17):2057-61. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.02.028.

32. Kriesel JD, Spruance J. Calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3) coadministered with influenza vaccine does not enhance humoral immunity in human volunteers. Vaccine. 1999 May 4;17(18):1883-8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00476-9.

33. Cooper C, Thorne A. Vitamin D supplementation does not increase immunogenicity of seasonal influenza vaccine in HIV-infected adults. HIV Clin Trials. 2011 Sep-Oct;12(5):275-6. doi: 10.1310/hct1205-275.

34. Principi N, Marchisio P, Terranova L, Zampiero A, Baggi E, Daleno C, et al. Impact of vitamin D administration on immunogenicity of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in previously unvaccinated children. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013 May;9(5):969-74. doi: 10.4161/hv.23540.

35. Lin CJ, Martin JM, Cole KS, Zimmerman RK, Susick M, Moehling KK, et al. Are children’s vitamin D levels and BMI associated with antibody titers produced in response to 2014-2015 influenza vaccine? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017 Jun 3;13(7):1661-5. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1299837.

36. Science M, Maguire JL, Russell ML, Smieja M, Walter SD, Loeb M. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and influenza vaccine immunogenicity in children and adolescents. PLoS One. 2014 Jan 29;9(1):e83553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083553.

37. Antonen JA, Hannula PM, Pyhala R, Saha HH, Ala-Houhala IO, Pasternack AI. Adequate seroresponse to influenza vaccination in dialysis patients. Nephron. 2000 May;85(1):56-61. doi: 10.1159/000045713.

38. Zitt E, Sprenger-Mähr H, Knoll F, Neyer U, Lhotta K. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with poor response to active hepatitis B immunisation in patients with chronic kidney disease. Vaccine. 2012 Feb 1;30(6):931-5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.086.

39. Aoun B, Dourthe ME, Davourie Salandre A, Souberbielle JC, Ulinski T. Do vitamin D plasma levels impact vaccine response in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome? Pediatr Nephrol. 2012 Oct;27(10):2161-2. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2273-y.

40. Peelen E, Rijkers G, Meerveld-Eggink A, Meijvis S, Vogt M, Cohen Tervaert JW, et al. Relatively high serum vitamin D levels do not impair the antibody response to encapsulated bacteria. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013 Jan;32(1):61-9. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1714-7.

41. Heine G, Drozdenko G, Lahl A, Unterwalder N, Mei H, Volk HD, et al. Efficient tetanus toxoid immunization on vitamin D supplementation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011 Mar;65(3):329-34. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.276.

42. Zheng Y, Li XG, Wang QZ, Ma AG, Bygbjerg IC, Sun YY, et al. Enhancement of vitamin A combined vitamin D supplementation on immune response to bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine revaccinated in Chinese infants. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014 Feb;7(2):130-5. doi: 10.1016/s1995-7645(14)60008-0.

43. Bahl R, Kumar R, Bhandari N, Kant S, Srivastava R, Bhan MK. Vitamin A administered with measles vaccine to nine-month-old infants does not reduce vaccine immunogenicity. J Nutr. 1999 Aug;129(8):1569-73. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.8.1569.

44. Benn CS, Balde A, George E, Kidd M, Whittle H, Lisse IM, et al. Effect of vitamin A supplementation on measles-specific antibody levels in Guinea-Bissau. Lancet. 2002 Apr 13;359(9314):1313-4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08274-0.

45. Sundaram ME, Meydani SN, Vandermause M, Shay DK, Coleman LA. Vitamin E, vitamin A, and zinc status are not related to serologic response to influenza vaccine in older adults: an observational prospective cohort study. Nutr Res. 2014 Feb;34(2):149-54. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2013.12.004.

46. Grzegorzewska AE, Jodłowska E, Mostowska A, Sowińska A, Jagodziński PP. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of vitamin D binding protein, vitamin D receptor and retinoid X receptor alpha genes and response to hepatitis B vaccination in renal replacement therapy patients. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014 Dec;13(12):1395-403. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2014.962521.

47. Van der Wielen M, Van Damme P, Chlibek R, Smetana J, von Sonnenburg F. Hepatitis A/B vaccination in adults over 40 years of age: Comparison of three vaccination schedules and effect of influencing factors. Vaccine. 2006 Jul 17;24(29-30):5509-15. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.04.016.