The recent updates issued by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on routine childhood immunization underscore the importance of evidence-based guidance to support effective disease prevention and equitable access to vaccination.

The proposed changes to routine childhood immunization recommendations reflect a shift in how certain vaccines are positioned within the national immunization framework. Rather than indicating concerns about vaccine safety or regulatory approval, these updates primarily affect the strength and scope of CDC recommendations, with some vaccines no longer included as part of routine use for all children. This distinction is important, as the underlying vaccines remain authorized and available, but their uptake may increasingly depend on individual clinical decision-making, state policies, insurance coverage, and public perception.

Such changes have the potential to introduce greater heterogeneity in vaccination coverage across populations and regions. While overall vaccination rates are unlikely to fall to zero, reduced uniformity in recommendations may weaken herd immunity for specific diseases, making outbreaks more sporadic and less predictable. The full public health impact remains difficult to estimate, particularly given that available data largely derive from pre-vaccination eras or from current effectiveness studies that assume higher baseline coverage than may exist under the revised framework.

In addition, alterations to CDC guidance can have downstream effects beyond U.S. borders, as CDC recommendations often inform global policy decisions, procurement strategies, and public confidence in vaccination programs. Taken together, these proposed changes underscore the need for careful monitoring, transparent communication, and continued emphasis on evidence-based decision-making to safeguard disease prevention efforts and promote equitable access to immunization.

The perspective portrayed on this article is rooted in rigorous scientific evaluation, global public-health principles, and the collective responsibility to protect children from preventable diseases. Without political affiliation, this statement is guided exclusively by the commitment to safeguarding pediatric health, maintaining high vaccination coverage, and ensuring that policy decisions remain aligned with the best available scientific evidence to mitigate potential public-health implications on disease prevention, vaccine confidence, and equitable access across diverse populations.

- Clarification: The FDA has not withdrawn these vaccines; what has changed is the CDC’s decision to no longer recommend them as part of routine immunization.

- Herd immunity variability: Coverage rates will not drop to zero, but herd immunity, though decreased, will become variable and unpredictable.

- Uncertainty: At this point, it is impossible to know the precise impact of this change.

- Limitations: The available data come from the pre-vaccination era and current effectiveness data, which limits accurate projections.

- Scope: We will address rotavirus, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and meningococcal disease. Discussing influenza currently is not feasible, as even a probable estimate is unrealistic under current uncertainty.

- Exclusion: comparisons with previous changes related to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination are not included.

- Globalization: The CDC’s “non-recommendation” position will likely have consequences beyond the United States— an impact that is currently impossible to quantify.

Rotavirus, implemented in 2006.

Impact of Rotavirus Vaccination in the United States (2000–2019)

From 2000 to 2019, childhood vaccination against rotavirus in the United States had the following impact:

- ~1.1 million fewer emergency department visits

- ~400,000 fewer hospitalizations

- ~1.2 billion dollars in medical costs avoided

- ~1,400 infant deaths prevented

Overall, rotavirus vaccination reduced the incidence of severe rotavirus disease in children by approximately 80%.

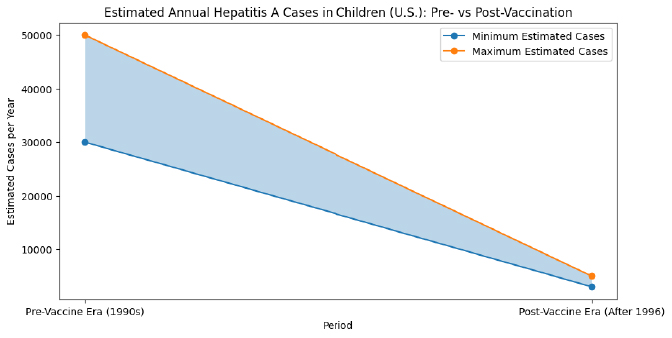

Hepatitis A, implemented in 1995.

Even with this great reduction of cases in children, there have been ongoing outbreaks of hepatitis A disease in the US since 2016, mostly spread through close personal contact in adults:

- 37 states affected

- More than 44,000 cases

- More than 400 deaths

A review of published studies evaluated the health outcomes, economic burden, and outbreak management considerations of US hepatitis A outbreaks since 2016.

Health Outcomes (33 studies), the most common adverse health outcomes from Hepatitis A disease were:

- Acute liver failure

- Liver transplantation

- Sepsis/septic shock

- Hepatic encephalopathy

Across studies, hepatitis A disease was reported to result in:

- Over 41% hospitalization rate

- Up to 11% case fatality rate

Economic Burden (10 studies), the estimated national average cost per hepatitis A-related hospitalization in 2017 was:

Over $16,000 per person

A 2017 outbreak resulted in:

$253 spent per employee evaluated for Hepatitis A exposure by a city health department.

What impact can we expect now without even vaccinating children?

Hepatitis B (HBV), implemented in 1994.

Vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV)—from mother to child—is highly efficient. In the absence of preventive interventions, transmission rates range from:

- 70–90% in HBeAg-positive mothers

- 10–40% in HBeAg-negative mothers

- Factors that contribute include:

- Mode of delivery

- Amniocentesis and other invasive obstetric procedures

- Breastfeeding

Since 1994, the first dose of the HBV vaccine has been administered within the first 24 hours of life. As a result, approximately 90,100 infant deaths have been prevented.

The birth dose is the only intervention that provides immediate protection for the newborn, even when maternal infection has not yet been detected.

Potential impact of discontinuing vaccination:

Projections show that without the HBV vaccine birth dose, between 18,000 and 20,000 babies per year in the United States would be born infected.

In the short term, this increase may not be immediately apparent, but the negative consequences would emerge over time.

Most of these babies would develop chronic HBV during childhood. As the years go by, these children would face an increased risk of:

- Liver cirrhosis

- Hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer)

- Liver failure and premature death

Suspending birth-dose vaccination would create a silent burden, with the most severe effects emerging decades later.

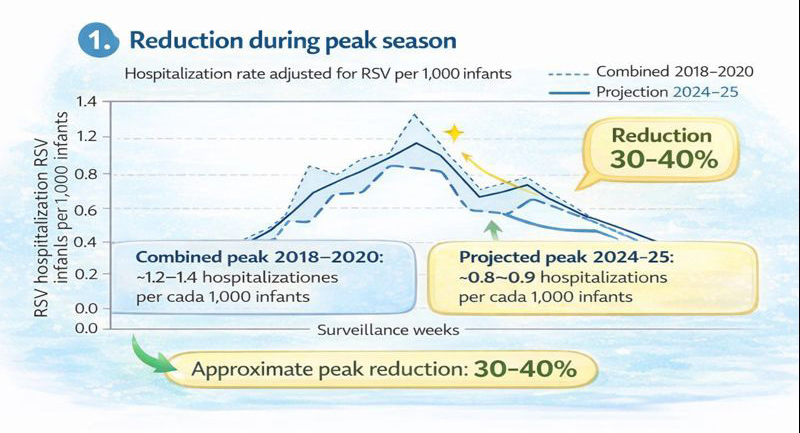

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), implemented in 2023.

The available data are relatively new. However, even with less than two years since its introduction, nirsevimab has already demonstrated a substantial reduction in RSV-related hospitalizations. Early surveillance reports consistently show meaningful decreases in seasonal peak admissions, reinforcing the real-world effectiveness of nirsevimab in preventing severe RSV disease among infants.

Serogroups A, C, W, Y Meningococcal Disease, implemented routinely in 2005 at 11-12 years old.

Adolescents and young adults are the primary transmitters of meningococcus.

This age group has the highest rates of nasopharyngeal carriage of Neisseria meningitidis, meaning they often carry the bacteria in the throat without showing symptoms. Through close social behaviors—including kissing, sharing drinks or utensils, living in close quarters, and attending crowded social events, they play a central role in spreading the bacteria to others, including infants and young children who are at much higher risk of severe disease.

Neisseria meningitidis can cause rapid, life-threatening infections such as meningitis and meningococcal septicemia, where early vaccination is crucial for prevention.

To reduce transmission and protect vulnerable populations, routine meningococcal vaccination has been recommended for adolescents at 11–12 years of age since 2005.

This strategy not only protects the vaccinated individual but also helps reduce community transmission, lowering the overall incidence of meningococcal disease.

Estimated Impact of the MenACWY Vaccine in the United States (2005–2021):

Between 2005 and 2021, MenACWY vaccination in the U.S. is estimated to have prevented:

Adolescents aged 11–15 years:

- 172 cases of invasive meningococcal disease (95% CI: 85–345)

- 16 deaths prevented (95% CI: 8–31)

- Young adults aged 16–23 years:

- 328 cases of invasive meningococcal disease (95% CI: 164–646)

- 38 deaths prevented (95% CI: 19–75)

Impact without vaccination:

Without the MenACWY vaccine, the cumulative incidence of invasive meningococcal disease in these age groups would have been at least 59% higher.

In total, without MenACWY vaccination, at least 54 deaths and around 500 additional cases of invasive meningococcal disease would have occurred among adolescents and young adults between 11 and 23 years of age.

Overall Consequences of Not Routinely Recommending Childhood Vaccination Against Rotavirus, Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B, RSV, and Meningococcal Disease:

If routine childhood vaccination against these pathogens is discontinued or no longer recommended, multiple serious consequences can be expected at the individual, community, and national levels. These consequences will not always be immediate. In many cases, the full impact will emerge gradually over years or decades.

Risks:

1. Increased disease incidence and outbreaks:

Without routine immunization, the incidence of all five vaccine-preventable diseases would rise. Outbreaks could become more frequent and more severe due to lower population immunity. This increase may occur:

- Rapidly (e.g., rotavirus, RSV, hepatitis A) due to seasonal circulation.

- Slowly but steadily (e.g., hepatitis B, meningococcal disease), with cases accumulating over time.

2. Loss of herd immunity and higher transmission:

Routine childhood vaccination is essential for maintaining herd immunity. Stopping routine vaccination would:

- Reduce overall immunity in the population.

- Allow silent transmission to increase.

- Increase risk for vulnerable individuals such as newborns, immunocompromised people, and older adults. (This effect is particularly significant for meningococcal disease and hepatitis A, which spread efficiently through asymptomatic carriers)

3. Increased hospitalizations and emergency visits:

All five diseases commonly lead to hospitalization in children. Without routine vaccination, the U.S. would likely see:

- More emergency visits for severe dehydration (rotavirus).

- Higher hospitalization rates in infants (RSV).

- More admissions due to fulminant hepatitis or liver failure (hepatitis A and B).

- Intensive care hospitalizations for meningococcal sepsis and meningitis.

- Hospital burden would rise seasonally and unpredictably.

4. Preventable deaths:

Each of these pathogens can cause fatal disease, which could occur quickly or decades later. The absence of routine vaccination would predictably increase:

- Infant and toddler deaths from rotavirus.

- Deaths from fulminant hepatic failure due to hepatitis A.

- Premature deaths from chronic hepatitis B progressing to cirrhosis or liver cancer.

- Infant deaths from severe RSV infection.

- Rapid, unexpected deaths from meningococcal septicemia or meningitis

5. Long-term complications and chronic disease:

Many of these infections increase lifetime healthcare needs and reduce quality of life and have long-term or permanent consequences:

- Chronic hepatitis B → lifelong infection, cirrhosis, liver cancer.

- Meningococcal disease → amputations, neurological disability, hearing loss.

- Severe RSV → recurrent wheezing, long-term pulmonary issues.

- Rotavirus → impaired nutrition and growth in severe or repeated cases.

6. Higher healthcare costs:

Economic analyses show that prevention is dramatically more cost-effective than managing outbreaks and chronic disease. Stopping routine immunization would increase:

- Emergency room visits.

- Hospital admissions.

- ICU stays.

- Use of antivirals, monoclonal antibodies, and long-term treatments.

- Public health outbreak responses.

7. Increased community spread from adolescents and adults:

When children are not vaccinated, adolescents and adults become the main carriers. This creates sustained reservoirs of infection, particularly relevant for:

- Meningococcal disease, spread through close contact.

- Hepatitis A, spread through person-to-person contact.

- RSV, which adults can transmit back to infants.

8. Delayed but severe long-term burden:

Some consequences would emerge only after many years, creating a hidden burden that becomes visible only when complications develop:

- Infant hepatitis B infections would progress to chronic disease.

- Chronic liver disease and liver cancer would rise decades later.

- Meningococcal carriage would increase silently until outbreaks occur.

- 9. Widening health inequities:

Out-of-pocket costs and prescription requirements would reduce access further. Removing routine vaccination disproportionately harms:

- Low-income families.

- Rural communities.

- Infants without regular medical access.

- Populations with higher baseline disease prevalence.

- 10. Decline in public trust and confusion:

- A shift in recommendations increases broader public-health risks and can lead to:

- Misinterpretation that vaccines are unsafe.

- Sharp drops in uptake of other routine vaccines.

- Increased vaccine hesitancy

Summary Statement

The consequences of not routinely vaccinating childhood against rotavirus, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, RSV, and meningococcal disease are not theoretical—they are measurable, predictable, and historically documented before vaccines existed. Routine vaccination remains the most effective strategy to protect children and the community. The United States could potentially face:

- Higher disease incidence

- More outbreaks

- Increased hospitalizations

- Preventable deaths

- Long-term disability and chronic illness

- Higher healthcare spending

- Greater transmission in unprotected communities

- A delayed but significant burden of severe disease

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood Immunization Schedule by Recommendation Group. https://www.hhs.gov/childhood-immunization-schedule/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acts on Presidential Memorandum to Update Childhood Immunization Schedule. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2026/2026-cdc-acts-on-presidential-memorandum-to-update-childhood-immunization-schedule.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rotavirus: Clinical Overview. https://www.cdc.gov/rotavirus/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Sustained decrease in laboratory detection of rotavirus after implementation of routine vaccination — United States, 2000–2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(13), 337–342. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6413a1.htm.

- Horn EK, Herrera-Restrepo O, Acosta AM, Simon A, Jackson B, Lucas E. The Burden of Hepatitis A Outbreaks in the United States: Health Outcomes, Economic Costs, and Management Strategies. J Infect Dis. 2024 Jul 25;230(1):e199-e218. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiae087.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023 Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis-surveillance-2023/about/index.html.

- American Public Health Association. (2023). Public health and policy experts urge the CDC to maintain universal newborn hepatitis B vaccination. https://www.apha.org/news-and-media/news-releases/apha-news-releases/public-health-and-policy-experts-urge-the-cdc-to-maintain-universal-newborn-hepatitis-b-vaccination.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Respiratory Syncytial Virus–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (RSV-NET): Hospitalization rates among children aged <5 years — United States, October 2018–April 2020 and October 2024–February 2025. CDC. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/74/wr/pdfs/mm7416-H.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Meningococcal vaccination: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/.

- Shin T, Wells CR, Shoukat A, Potter-Schwartz L, Langevin E, Langley JM, Galvani AP, Moghadas SM. Quadrivalent Conjugate Vaccine and Invasive Meningococcal Disease in US Adolescents and Young Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Nov 4;7(11):e2443551. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.43551.