Introduction:

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is caused by two lentiviruses—human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 (HIV-1 and HIV-2)—both originating from multiple cross-species transmissions of simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) naturally infecting African primates. While most of these transmissions led to limited human spread, one event involving SIVcpz from chimpanzees in southeastern Cameroon gave rise to HIV-1 group M, the principal driver of the global AIDS pandemic.

AIDS was first recognized in 1981, when increasing numbers of young men who have sex with men developed unusual opportunistic infections and rare malignancies, revealing a previously unknown immune deficiency syndrome.

Despite major advances in antiretroviral therapy that have transformed HIV infection into a manageable chronic disease, the epidemic remains ongoing worldwide. Both high-income and low- and middle-income countries continue to be affected, with the greatest burden in the latter due to limited access to healthcare and treatment. In the absence of an effective preventive vaccine, HIV/AIDS remains a major global public health challenge, carrying profound human, social, and economic consequences.

Global HIV statistics up to 2024:

- 40.8 million [37.0 million–45.6 million] people globally were living with HIV in 2024.

- 1.3 million [1 million–1.7 million] people became newly infected with HIV in 2024.

- 630 000 [490 000–820 000] people died from AIDS-related illnesses in 2024.

- 31.6 million people [27.8–32.9 million] were accessing antiretroviral therapy in 2024.

- 91.4 million [73.4 million–116.4 million] people have become infected with HIV since the start of the epidemic.

- At the end of 2024, US$ 18.7 billion was available for the AIDS response in low- and middle-income countries—17% below the US$ 21.9 billion needed annually by 2030 to stay on track to end AIDS as a public health threat.

General recommendations:

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disrupts immune function primarily by depleting CD4 T lymphocytes, compromising both humoral and cellular immunity. Although combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has transformed HIV care, enabling most patients to achieve undetectable viral loads and adequate CD4 counts, significant immune function differences persist. Immune recovery can be incomplete in patients with low nadir CD4 counts or delayed initiation of cART, due to inadequate CD4 cell reconstitution and additional defects in cell-mediated and humoral immunity.

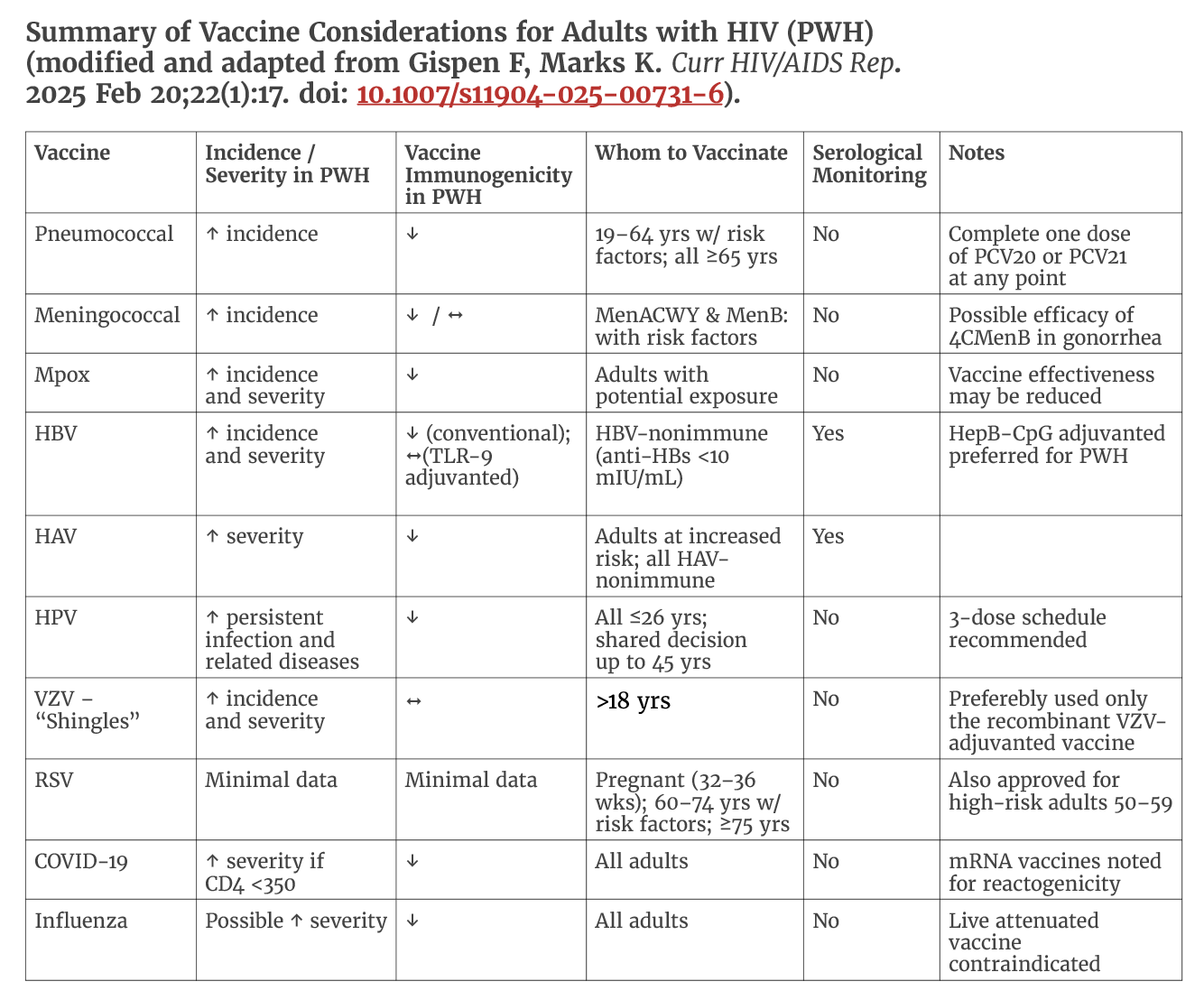

Immunizations are a critical component for people living with HIV (PWH), as immunodeficiency increases susceptibility to vaccine-preventable diseases and the risk of severe outcomes. However, HIV-related immune suppression may reduce the ability to mount or sustain adequate vaccine-induced immunity, and live vaccines can pose safety concerns in this population.

Vaccine responses are often diminished in individuals with advanced HIV infection, particularly those with CD4 counts <200 cells/mm³ or HIV RNA levels ≥200 copies/mL and may wane more rapidly than in individuals without HIV. Monitoring immunogenicity and determining the need for booster doses remain important aspects of vaccine management in people with HIV.

Inactivated vaccines are generally safe, though rare adverse effects cannot be completely excluded. In contrast, live attenuated vaccines are relatively contraindicated for patients with CD4 counts <200 cells/mm³ due to the risk of severe reactions. For those with CD4 counts ≥200 cells/mm³, inactivated formulations—such as for polio, influenza, typhoid, and zoster—are preferred. Live vaccines should be used only when no inactivated alternative exists and when the benefit of protection outweighs the potential risk.

Given the unique immunologic and clinical characteristics of PWH, vaccination guidelines differ in several important ways from those established for the general population. This section summarizes the most recent updates to these recommendations, integrates emerging data on vaccine safety, immunogenicity, and effectiveness in PWH, and discusses persisting gaps in knowledge that warrant further investigation.

Accordingly, vaccine recommendations for PWH differ from those for the general population regarding timing, dosing, and the need for serologic response monitoring. In addition, newly available vaccines are now recommended for PWH to prevent invasive pneumococcal disease, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), COVID-19, mpox, Herpes Zoster, and hepatitis B virus (HBV).

Vaccination in Low Resource Settings:

In low-resource settings, PWH should receive routine and recommended vaccinations like the annual flu shot and Tdap vaccine, along with the Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B, and Pneumococcal vaccines, prioritizing those that are most effective and accessible. Specific recommendations may be adjusted based on individual risk factors, immune status, and vaccine availability, which requires a collaborative decision with a healthcare provider.

Considerations for low-resource settings

- Prioritize based on risk: Focus on the most critical and accessible vaccines, such as influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, which are vital for protecting people with HIV from severe illness.

- Address specific needs: Consider travel to endemic areas, which may require additional vaccinations like the Hepatitis A and yellow fever vaccines.

- Ensure access: Work with healthcare providers to ensure timely access to routine and urgent medical care and vaccines, including through patient-centered approaches and low-barrier models like telehealth or mobile clinics.

- Manage immune status: When considering live attenuated vaccines like MMR or varicella, carefully assess a patient’s immune status, prioritizing those with higher CD4 counts and stable viral loads.

- Consider cost and logistics: Adjust vaccination schedules based on the availability and affordability of different vaccines in the local context. For example, the double-dose Hepatitis B vaccine regimen may improve immunogenicity and seroconversion rates.

Travel and Vaccination Considerations for PWH:

All travelers should be up to date with routine immunizations before departure, regardless of destination. For those planning international travel, additional vaccines may be indicated based on regional disease risk, such as cholera, yellow fever, typhoid, or Japanese encephalitis.

For individuals living with HIV, pre-travel consultation with a healthcare provider experienced in immunization of immunocompromised patients is essential. Most travel-related vaccines are safe for people with HIV, although vaccine efficacy may be reduced, particularly among those with advanced immunosuppression. In such cases, clinicians may recommend serologic testing to assess post-vaccination immunity or suggest additional doses or alternative preventive measures to ensure adequate protection.

Certain travel vaccines are live-attenuated and generally contraindicated in individuals with CD4 counts <200 cells/mm3 due to the risk of vaccine-associated complications. However, in specific high-risk travel situations, the benefit of protection may outweigh potential risks. Decisions regarding live vaccines should be individualized, balancing disease exposure risk, immune status, and availability of alternative protective measures.

Conclusions:

The HIV/AIDS epidemic is approaching its fifth decade. Advances in combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in high-resource settings have transformed HIV infection into a chronic, manageable condition. However, despite achieving viral suppression and normal CD4+ T-cell counts, people with HIV (PWH) often experience persistent immune dysregulation and incomplete immune restoration.

In the absence of a preventive HIV vaccine in the short to mid-term, tailored vaccination strategies for this unique population—now exceeding 40 million individuals globally—are essential. Moreover, many PWH in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) remain without access to cART, leaving them highly vulnerable to both opportunistic and non-opportunistic infections. A sustained global effort is urgently needed to expand treatment access and, concurrently, to strengthen and promote immunization programs specifically designed for this population.

Bibliography:

- Sharp PM, Hahn BH. Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011 Sep;1(1):a006841. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006841.

- Smith JH, Whiteside A. The history of AIDS exceptionalism. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010 Dec 3;13:47. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-47.

- UNAIDS: Global HIV & AIDS statistics – Fact Sheet. (Accessed December 10, 2025). https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet#:~:text=Global%20HIV%20statistics,with%20HIV%20accessing%20antiretroviral%20therapy.

- Faria NR, Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Baele G, Bedford T, Ward MJ, Tatem AJ, Sousa JD, Arinaminpathy N, Pépin J, Posada D, Peeters M, Pybus OG, Lemey P. HIV epidemiology. The early spread and epidemic ignition of HIV-1 in human populations. Science. 2014 Oct 3;346(6205):56-61. doi: 10.1126/science.1256739.

- Gispen F, Marks KM. Update on Vaccination Recommendations for Adults with HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2025 Feb 20;22(1):17. doi: 10.1007/s11904-025-00731-6.

- Kerr C, Dyer M, Urban MA, Vail RM, Shah SS, Fine SM, McGowan JP, Merrick ST, Radix AE, Monroe AK, Rodrigues J, Hoffmann CJ, Norton BL, Gonzalez CJ. Immunizations for Adults With HIV [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins University; 2025 Apr. PMID: 38051793.

- HIV.gov: Vaccines and people with HIV. (Accessed December 8, 2025). https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/staying-in-hiv-care/other-related-health-issues/immunizations-recommended-for-people-living-with-hiv#:~:text=Based%20on%20age%20or%20other,have%20any%20serious%20side%20effects.

- CDC: Travelers with HIV. (Accessed December 7, 2025). https://www.cdc.gov/yellow-book/hcp/travelers-with-additional-considerations/travelers-with-hiv.html.

- CDC: Adult Immunization Schedule by Medical Condition and Other Indication (Addendum updated August 7, 2025). Recommendations for Ages 19 Years or Older, United States, 2025. (Accessed December 7, 2025). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/imz-schedules/adult-medical-condition.html.

- Trkola A, Moore PL. Vaccinating people living with HIV: a fast track to preventive and therapeutic HIV vaccines. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024 Apr;24(4):e252-e255. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00481-4.